A portrait of Mahler as maker of worlds and emblem of ours

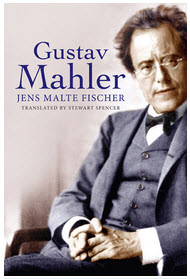

Review: “Gustav Mahler,” by Jens Malte Fischer. English language edition. Yale University Press, 766 pages, $50. ****

By Lawrence B. Johnson

A hundred years after his death, the music and the mystique of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) hold sway in concert halls to a degree that the composer himself might not have envisioned, even in his declaration that “my time will come.” It’s fair to say Mahler’s vast symphonies have displaced Beethoven’s as the conductor’s touchstone, if not as the authentic paragon of works in that form. It is beyond dispute that in their epic narratives, fraught with irony and angst, Mahler’s symphonies connect with – indeed prefigure – our time.

A hundred years after his death, the music and the mystique of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) hold sway in concert halls to a degree that the composer himself might not have envisioned, even in his declaration that “my time will come.” It’s fair to say Mahler’s vast symphonies have displaced Beethoven’s as the conductor’s touchstone, if not as the authentic paragon of works in that form. It is beyond dispute that in their epic narratives, fraught with irony and angst, Mahler’s symphonies connect with – indeed prefigure – our time.

And so their author’s hold on our imagination, our curiosity and perhaps our sense of identification has only tightened in the half-century since a confluence of circumstances catapulted Mahler from the periphery of public awareness to the center of attention. In the late 1950s, in the midst of the cold war, the charismatic Leonard Bernstein became music director of the New York Philharmonic and thus acquired an ideal forum from which to advocate his devout enthusiasm for Mahler; and at virtually the same time came stereo recording with its clarifying perspective on the complex fabric of Mahler’s works.

Yet despite the plethora of recordings and concert performances, this Mahlerian immersion of the last half-century, a veil of myth and mysticism continues to obscure the composer who famously described himself as “thrice homeless, as a Bohemian in Austria, an Austrian among Germans, and a Jew throughout the world.” It is the lifting of that veil, in personal and thoughtful fashion, that gives ultimate value to Jens Malte Fischer’s “Gustav Mahler,” newly brought to the English-speaking world in a translation by Stewart Spencer.

Fischer, professor of theater history at the University of Munich and frequent writer on musical subjects, notably singers, combines in his portrait of Mahler the labors of biographer, musical analyst and, to a degree, psychoanalyst. The original, German-language edition of “Gustav Mahler” was published in 2003. On the YaleBooks website, Fischer writes :

The extreme highs and lows of Mahler’s life were not easy to describe for an author like myself, writing about his hero. The composer’s life had signs of tragedy, well known today to readers, but sometimes this tragic account is too one-sided and some people forget that Mahler also had periods of pure delight in his life, specifically in his role as perhaps the most famous and acclaimed opera conductor both in Vienna (and) in New York. Let us not forget that it was Mahler’s role as composer that attracted controversy, not his role as a conductor and opera performer at the Vienna Court Opera, for which he was revered.

In constructing a biography of his “hero,” Fischer manages to be clear of both eye and plan. Only in setting out the composer’s youthful development – his childhood amid the military bands and gypsy music in the Austrian outback village of Iglau, his student days at the Vienna Conservatory, his early ascent as chief conductor at assorted small-town opera houses – does Fischer stick to a chronological narrative.

With Mahler’s arrival at the Hamburg Opera in 1891, his last stop before he sprang to Vienna and the top of the operatic world, Fischer switches from direct chronology to topical essays: Mahler’s Jewishness, his life-long struggle with illness, the cultural and political milieu of 1900 Vienna, the background and character of his future wife Alma Schindler, his contemplations of faith and philosophy, the life-altering crises of the single year 1907, his escape to New York and his seasons at the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic.

Between essays, which bear a kind of chronological counterpoint, Fischer pauses to comment on the symphonies in sequence. It is in the essays that Fischer’s enthusiasm for his subject and his analytical skills shed the most engaging, and provocative, light.

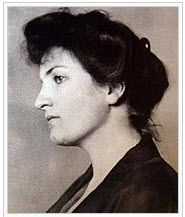

The author has very little good to say about Alma Schindler Mahler, by all accounts the most beautiful woman in Vienna when at age 21 she married to 40-year-old composer. In Fischer’s view, Mahler’s friends and Alma’s parents were right in warning that it was a bad match. While Alma was very bright, says Fischer, she was also naïve and vain and no intellectual match for Mahler, a voracious reader with a passion for philosophy.

The author has very little good to say about Alma Schindler Mahler, by all accounts the most beautiful woman in Vienna when at age 21 she married to 40-year-old composer. In Fischer’s view, Mahler’s friends and Alma’s parents were right in warning that it was a bad match. While Alma was very bright, says Fischer, she was also naïve and vain and no intellectual match for Mahler, a voracious reader with a passion for philosophy.

Mahler’s intellectual zeal was only typical of his whole-hearted engagement with every aspect of his life. He loved to hike, bicycle, row and swim. It was only after a chance diagnosis of his congenitally flawed heart, when he was 46 in1907, that he abandoned his daily physical regimen; and even then he resumed exercise when he discovered that backing off only made him feel lethargic.

Mahler suffered from throat ailments throughout his life, but gave in to sickness rarely and grudgingly. Nor does Fischer believe Mahler was preoccupied with death. Mahler reveled in life; and if the late song-symphony “Das Lied von der Erde” and the Ninth Symphony sound like valedictories, they are art works, not testaments, the author notes. Mahler the artist went straight from the canvas of the Ninth Symphony to sketching out the Tenth.

Fischer’s observations on the Tenth Symphony should be required reading for every conductor. The short of it is: There is no Tenth Symphony, beyond the substantially completed opening movement. So-called completions of the Tenth are intellectual exercises, not creations for the concert hall. Sir Georg Solti, former music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra,, once explained why he would not conduct imagined realizations of the Tenth: because there is none of Mahler’s characteristic counterpoint. All one need do is listen to the Ninth, then any version of the Tenth to grasp what is missing.

By the latter chapters of Fischer’s highly readable book, you feel you’ve come to know Mahler as man and artist, at least in the sense of comprehending what drove him, what excited and inspired him. Mahler thought of his sprawling symphonies as the most efficient of creations, each with its place in the cosmos, a world unto itself. His life was a mission, like that of any artist. But while the whole musical world could grasp the greatness of Mahler in the opera house, few could wrap themselves around his bizarre symphonies, dappled as they were with the sunlight and shadows of life’s own contradictions.

The composer did have his admirers, even his acolytes and enduring champions, notably his conducting protégé Bruno Walter and Willem Mengelberg, chief conductor of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. But it has only been since Bernstein that Mahler has come into his time.

The composer did have his admirers, even his acolytes and enduring champions, notably his conducting protégé Bruno Walter and Willem Mengelberg, chief conductor of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. But it has only been since Bernstein that Mahler has come into his time.

Which brings me to Fischer’s curious epilogue: a litany of all the important conductors of the modern era who have taken Mahler to their hearts and another list of those who have not. The two lists smack vaguely of the blessed and the damned. Then he closes, in flourish of Wagnerian ecstasy, with the positing of “a Mahler wound, which will not close as long as human society lacks the desire for reconciliation.”

Personally, I find the notion a bit disheartening that when we all finally decide to get along, Mahler’s glorious Second Symphony, the masterfully concise Fifth, the shadowy Seventh, the transcendent Ninth will all suddenly become superfluous, irrelevant and forgotten.

I find more depth, more that bespeaks the compelling quality of Fisher’s book end to end, in this thought offered a few lines earlier: “Mahler remains a problematic phenomenon.” Indeed, he does. And so do we all, and therein lies our bond with him.

Related link:

- Listen to Bernstein’s Mahler recordings: Go to AllMusic.com

- Purchase “Gustav Mahler” by Jens Malte Fischer: Go to Amazon.com

Tags: Alma Schindler Mahler, Gustav Mahler, Jens Malte Fischer

No Comment »

4 Pingbacks »

[…] “Gustav Mahler,” English-language translation of the biography by Jens Malte Fischer: Read the book review […]

[…] “Gustav Mahler,” English-language translation of the biography by Jens Malte Fischer: Read the book review […]

[…] On the Aisle reviews Jens Malte Fischer’s biography of Mahler: Read the review here. Photos and credits: Home page and top: Esa-Pekka Salonen. (Photo by Snezana Vucetic Bohm). […]

[…] On the Aisle reviews Jens Malte Fischer’s biography of Mahler: Read the review here. Photos and credits: Home page and top: Esa-Pekka Salonen. (Photo by Snezana Vucetic Bohm). […]